Strategic Plan

Planning is bringing the future into the present so that you can do something about it now

— Alan Lakein

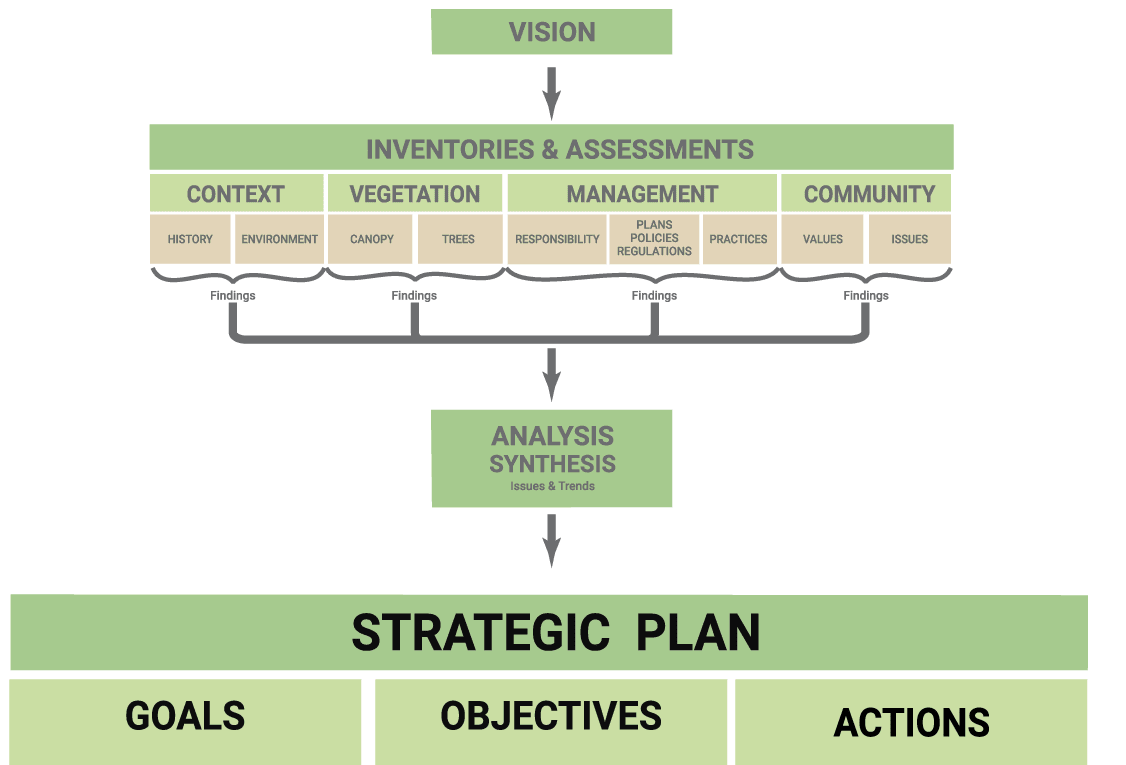

The strategic planning portion of the Urban Forest Management Plan includes the development of goals, objectives, and actions that will lead to the achievement of your vision for the future of the urban forest. The strategic planning process begins with the analysis of the data collected from Inventories and Assessments.

As you analyze the data that you collected from inventories and assessments, try to determine how the urban forest arrived at its current state. For instance, why is canopy cover decreasing? It could be because more trees are being removed than are planted or an invasive pest is killing trees at an accelerated rate.

Issues and Trends

You can project what the urban forest is likely to look like in the future based on current conditions and practices. For example: If small-statured trees (e.g., crape myrtles) have been planted to replace large trees (e.g., coast live oaks), tree canopy cover may not be restored even when new trees reach their mature size.

One way to organize the data analysis and synthesis is to consider the needs related to major urban forestry program areas. It might help you to refer to criteria for urban forest sustainability for each:

| Canopy cover | Achieve climate appropriate tree cover, community-wide. | Though the ideal amount of canopy cover will vary by climate and region (and perhaps by location within the community, there is an optimal degree of cover for every city. |

| Age distribution | Provide for uneven age distribution. | A mix of young and mature trees is essential if canopy cover is to remain relatively constant over time. To insure sustainability, an on-going planting program should go hand in hand with the removal of senescent trees. Some level of tree inventory will make monitoring for this indicator easier. Small privately owned properties pose the biggest challenge for inclusion in a broad monitoring program. |

| Species mix | Provide for species diversity | Species diversity is an important element in the long-term health of urban forests. Experience with species-specific pests has shown the folly of depending upon one species. Unusual weather patterns and pests may take a heavy toll in trees in a city. It is often recommended that no more than 10 percent of a city’s tree population consist of one species. |

| Native vegetation | Preserve and manage regional biodiversity. Maintain the biological integrity of native remnant forests. Maintain wildlife corridors to and from the city. | Where appropriate, preserving native trees in a community adds to the sustainability of the urban forest. Native trees are well-adapted to the climate and support native wildlife. Replanting with nursery stock grown from native stock is an alternative strategy. Planting nonnative, invasive species can threaten the ability of native trees to regenerate in greenbelts and other remnant forests. Invasive species might require active control programs. |

Adapted from: James R. Clark, Nelda P. Matheny, Genni Cross and Victoria Wake, A Model of Urban Forest Sustainability, Journal of Arboriculture 23(1): January 1997, Web, http://naturewithin.info/Policy/ClarkSstnabltyModel.pdf, 9 Sept 2015.

| Citywide management plan | Develop and implement a management plan for trees on public and private property. | A citywide management plan will add to an urban forest’s sustainability by addressing important issues and creating a shared vision for the future of the community’s urban forest. Elements may include: species and planting guidelines; performance goals and standards for tree care; requirements for new development (tree preservation and planning); and specifications for managing natural and open space areas. |

| Funding | Develop and maintain adequate funding to implement a citywide management plan. | Since urban forests exist on both public and private land, funding must be both public and private. The amount of funding available from both sources is often a reflection of the level of education and awareness within a community for the value of its urban forest. |

| Staffing | Employ and train adequate staff to implement a citywide management plan. | An urban forest’s sustainability is increased when all city tree staff, utility and commercial tree workers and arborists are adequately trained. Continuing education in addition to initial minimum skills and/or certifications desirable. |

| Assessment tools | Develop methods to collect information about the urban forest on a routine basis. | Using canopy cover assessment, tree inventories, aerial mapping, geographic information systems a and other tools, it is possible to monitor trends in a city’s urban forest resource over time. |

| Species and site selection | Provide guidelines and specifications for species use, on a context-defined basis. | Providing good planting sites and appropriate trees to fill them is crucial to sustainability. Allowing adequate space for trees to grow and selecting trees that are compatible with the site will reduce the long- and short-term maintenance requirements and enhance their longevity. Avoiding species known to cause allergenic responses is also important in some areas. |

| Standards for tree care | Adopt and adhere to professional standards for tree care. | Adhering to the professional standards such as the Tree Pruning Guidelines (ISA) and ANSI Z133 publications will enhance sustainability. |

| Citizen safety | Maximize public safety with respect to trees. | In designing parks and other public spaces, public safety should be a key factor in placement, selection, and management of trees. Regular inspections for potential tree hazards are an important element in the management program. |

| Recycling | Create a closed system for tree waste. | A sustainable urban forest is one that recycles its products by composting, reusing chips as mulch and/or fuel and using wood products as firewood and lumber. |

Adapted from: James R. Clark, Nelda P. Matheny, Genni Cross and Victoria Wake, A Model of Urban Forest Sustainability, Journal of Arboriculture 23(1): January 1997, Web, http://naturewithin.info/Policy/ClarkSstnabltyModel.pdf, 9 Sept 2015.

| Public agency cooperation | Ensure all city departments operate with common goals and objectives. | Departments such as parks, public works, fire, planning, school districts and (public) utilities should operate with common goals and objectives regarding the city’s trees. Achieving this cooperation, requires involvement of the city council and city commissions. |

| Involvement of large private and institutional landholders | Large private landholders embrace city-wide goals and objectives through specific resource management plans. | Private landholders own and mange most of the urban forest. Their interest in, and adherence to, resource management plans is most likely to result from a community-wide understanding and valuing of the urban forest. In all likelihood, their cooperation and involvement cannot be mandated. |

| Green industry cooperation | The green industry operates with high professional standards and commits to city-wide goals and objectives.

|

From commercial growers to garden centers and from landscape contractors to engineering professionals, the green industry has a tremendous impact on the health of a city’s urban forest. The commitment of each segment of this industry to high professional standards and their support for city-wide goals and is necessary to ensure appropriate planning and implementation. |

| Neighborhood Action | At the neighborhood level, citizens understand and participate in urban forest management. | Neighborhoods are the building blocks of cities. They are often the arena where individuals feel their actions can make the biggest difference in their quality of life. Since the many urban trees are on private property (residential or commercial), neighborhood action is a key to urban forest sustainability. |

| Citizen/government/

business interaction |

All constituencies in the community interact for the benefit of the urban forest. | Having public agencies, private landholders, the green industry and neighborhood groups all share the same vision of the city’s urban forest is a crucial part of sustainability. This condition is not likely to result from legislation. It will only result from a shared understanding of the urban forest’s value to the community and commitment to dialogue and cooperation among the stakeholders. |

| General awareness of

trees as a community resource |

The public understands the value of trees to the community. | Fundamental to the sustainability of a city’s urban forest is the public’s understanding of the value of its trees. People who value trees elect officials who value trees. In turn, officials who value trees are more likely to require the agencies they oversee to maintain high standards for management and provide adequate funds for implementation. |

| Regional cooperation | Provide for cooperation and interaction among neighboring communities and regional groups.

|

Urban forests do not recognize geographic boundaries. Linking city’s efforts to those of neighboring communities enables consideration and action on larger geographic and ecological issues, such as water quality and air quality. |

Adapted from: James R. Clark, Nelda P. Matheny, Genni Cross and Victoria Wake, A Model of Urban Forest Sustainability, Journal of Arboriculture 23(1): January 1997, Web, http://naturewithin.info/Policy/ClarkSstnabltyModel.pdf, 9 Sept 2015.

Many urban forestry issues combine aspects that involve two or all three of these program areas.

Vegetation — Tree Resource Needs

Consider needs related to the tree resource itself and processes that maintain the forest, including:

- More species and age diversity

- Better maintenance of existing trees

- Fewer hazardous trees

- Compatibility of species with climate and planting sites

- Control of diseases and invasive pests

- More tree plantings and where

Management Needs

Consider the needs of the urban forest program and the people involved with the short and long-term care and maintenance of the urban forest.

- Improved ability to schedule and track projects and maintenance

- Better coordination between departments with respect to tree issues

- Updated municipal tree ordinances

- Adequate staffing

- More training and education for tree program staff

- Alternative and stable source of program funding

- Creation of a tree board

- Updated species selection lists or criteria

Community Needs

Consider needs related to how the public perceives and interacts with the urban forest and the urban forest management program including:

- Better understanding among residents about proper tree selection placement, planting, and care

- Guidelines and ordinances to promote protection of existing trees

- Enforcement of quality ordinances

- Licensing of local tree care contractors to improve compliance with approved tree care standards

- Public education and awareness about the benefits of trees and sustainable urban forest management practices

- Programs to improve tree care in commercial landscapes

When you have completed the data analysis and synthesis, you should have an understanding of why your urban forest is in its current state.

What issues and trends have been identified relative to:

- tree & vegetation resources,

- management,

- and community interactions?

What practices would need to be continued or changed to maintain or expand the existing urban forest?

What management actions would be needed to reach target canopy levels?

Is awareness and education needed regarding urban forest benefits, management, and tree care?

Many people fail in life, not for lack of ability or brains or even courage, but simply because they have never organized their energies around a goal.

— Elbert Hubbard

Goals are summative statements that spell out the overall general outcomes that you seek to achieve. Develop broad goals that address the needs you have identified.

What do you want? What would be the elements of a highly successful UFMP?

Make goals tangible and quantifiable. If you are explicit in stating your goals (e.g., attain 35 percent canopy cover by the year 2020), it will be easier to evaluate your progress. Create [itg-glossary glossary-id=”382″]SMART[/itg-glossary] goals.

What would have to happen in terms of tree resources, management, and community programs to bring your vision for the urban forest to reality?

You might find it helpful to review Criteria and Performance Indicators for urban forest sustainability for each program area:

| Criteria | Low Performance | Moderate Performance | Good Performance | Optimal Performance | Key Objective |

| Canopy cover | No assessment | Visual assessment (photographic) | Sampling of tree cover using aerial photographs | Information on urban forests included in citywide geographic information system (GIS) | Achieve climate-appropriate degree of tree cover, community-wide. |

| Age – distribution of trees in community | No assessment | Street tree inventory (complete or sample) | Public/private sampling | Included in citywide geographic information system (GIS) | Provide for uneven age distribution. |

| Species mix | No assessment | Street tree inventory | Citywide assessment of species mix | Included in citywide geographic information system (GIS) | Provide for species diversity. |

| Native vegetation | No program of integration | Voluntary use on public projects | Requirements for use of native species on a project appropriate basis | Preservation of regional biodiversity | Preserve and manage regional biodiversity. Maintain the biological integrity of native remnant forests. Maintain wildlife corridors to and from the city. |

Adapted from: James R. Clark, Nelda P. Matheny, Genni Cross and Victoria Wake, A Model of Urban Forest Sustainability, Journal of Arboriculture 23(1): January 1997, Web, http://naturewithin.info/Policy/ClarkSstnabltyModel.pdf, 9 Sept 2015.

| Criteria | Low Performance | Moderate Performance | Good Performance | Optimal Performance | Key Objective |

| Citywide management plan | No plan | Existing plan limited in scope and implementation | Government wide plan, accepted and implemented | Citizen/

government/ business resource management plan, accepted and implemented |

Develop and implement a management plan for trees and forests on public and private property. |

| Citywide funding | Funding by crisis management | Funding to optimize existing population | Adequate funding to provide for net increase in population and care | Adequate funding, private and public, to sustain maximum potential benefits | Develop and maintain adequate funding to implement a citywide management plan. |

| City staffing | No staff | No training | Certified arborists on staff | Professional tree care staff | Employ and train adequate staff to implement citywide management plan. |

| Assessment tools | No ongoing program of assessment | Partial inventory | Complete inventory | Information on urban forests included in citywide GIS | Develop methods to collect information about the urban forest on a routine basis. |

Adapted from: James R. Clark, Nelda P. Matheny, Genni Cross and Victoria Wake, A Model of Urban Forest Sustainability, Journal of Arboriculture 23(1): January 1997, Web, http://naturewithin.info/Policy/ClarkSstnabltyModel.pdf, 9 Sept 2015.

| Criteria | Low Performance | Moderate Performance | Good Performance | Optimal Performance | Key Objective |

| Public agency cooperation | Conflicting goals among departments | No cooperation | Informal working teams | Formal working teams with staff coordination | Insure all city departments operate with common goals and objectives. |

| Involvement of large private and institutional landholders | Ignorance of issue | Educational materials and advice available to landholders | Clear goals for tree resource by private land holders; incentives for preservation of private trees | Land-holders develop comprehensive tree management plans (including funding) | Large private landholders embrace citywide goals and objectives through specific resource management plans. |

| Green industry cooperation | No cooperation among segments of industry (nursery, contractor, arborist). No adherence to industry standards | General cooperation among nurseries – contractors – arborists | Specific cooperative arrangements such as purchase certificates for right tree, right place | Shared vision and goals including the use of professional standards | The green industry operates with high professional standards and commits to citywide goals and objectives. |

| Neighborhood Action | No action | Isolated and/or limited number of active groups | Citywide coverage and interaction | All neighborhoods organized and cooperating | At the neighborhood level, citizens understand and participate in urban forest management. |

| Citizen/ government/ business interaction | Conflicting goals among constituencies | No interaction among constituencies | Informal and/or general cooperation | Formal interaction, e.g., tree board with staff coordination | All constituencies in the community interact for the benefit of the urban forest. |

| General awareness of trees as a community resource | Trees are problems and a drain on budgets. | Trees are important to the community | Awareness that trees provide environmental benefits | Trees are vital components of the economy and environment | The public understands the value of trees to the community. |

| Regional cooperation | Communities operate independently | Communities share similar policy vehicles | Regional planning | Regional planning coordination and/or management plans | Provide for cooperation and interaction among neighboring communities and regional groups. |

Adapted from: James R. Clark, Nelda P. Matheny, Genni Cross and Victoria Wake, A Model of Urban Forest Sustainability, Journal of Arboriculture 23(1): January 1997, Web, http://naturewithin.info/Policy/ClarkSstnabltyModel.pdf, 9 Sept 2015.

Use the following examples of goals as a starting point for thinking about, and formulating your organization’s goals:

- Improve the quality of the community forest (consisting of all public and private trees) over time, in ways that will optimize environmental, economic, habitat, food, and social benefits to the city and its neighborhoods.

- Establish and maintain optimal levels of canopy cover to maximize ecosystem benefits provided by the urban forest, (maintain air quality, reduce energy use, moderate storm water runoff, and provide a favorable environment for city residents).

- Select, situate, and maintain urban trees appropriately to maximize benefits and minimize hazard, nuisance, hardscape damage, and maintenance costs.

- Develop a citywide urban forest master tree planting plan.

- Adopt an Urban Forest Management Plan to guide long-term tree planting and maintenance activities and efficient and cost-effective management of the urban forest. Update the plan every five years.

- Centralize tree management under the urban forester and coordinate tree-related activities through this position.

- Support outreach efforts to educate city staff, the business community, and the public about the environmental, social, and economic benefits of trees.

- Provide awareness of the importance of the community forest; educate the community on proper tree planting and care; and encourage greater participation in tree planting and stewardship activities.

Goals need to include the concerns and desires of the [itg-glossary glossary-id=”112″]stakeholders[/itg-glossary]. General consensus on the management plan’s goals can help ensure that necessary resources will be made available to implement the plan. If funding is limited, goals should be prioritized so that resources can be directed toward the most important or urgent goals first.Priority rankings are also used to phase activities over time so that high priority tasks are completed before low priority tasks. For example, dealing with a backlog of potentially hazardous trees may be the highest priority in the first years of the plan. Once the backlog has been cleared out, other actions (such as replanting after tree removals) may have the highest priority.

Priority rankings are also used to phase activities over time so that high priority tasks are completed before low priority tasks. For example, dealing with a backlog of potentially hazardous trees may be the highest priority in the first years of the plan. Once the backlog has been cleared out, other actions (such as replanting after tree removals) may have the highest priority.

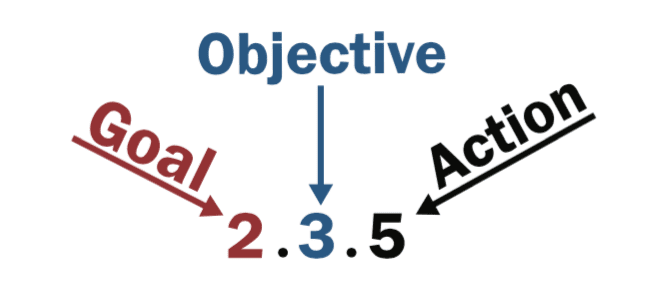

Like goals, objectives are desired outcomes, but objectives are more specific and limited in scope. Goals set the overall outcomes that are envisioned by the plan. Objectives provide more specificity by breaking goals into the components.

For example, suppose you set a goal to increase canopy cover from 20 to 30 percent within 10 years. This goal is explicit and quantifiable, but doesn’t indicate what needs to be done. To reach the target canopy cover for the goal stated below, you would need to follow the objectives.

Establish and maintain optimal levels of tree canopy and other vegetative cover to maximize ecosystem benefits provided by the urban forest. Increase canopy cover from 20 to 30 percent within 10 years.

Objective 1.1

Maintain most or all of the existing canopy cover through proper tree maintenance and protection of existing trees.

Objective 1.2

Plant additional trees and allow existing small trees to grow and expand their canopy cover.

Some objectives can contribute to the realization of two or more related goals. For instance, tree planting can contribute to both canopy cover and increased age diversity in the urban forest. In that case, you can cite a given objective under multiple goals to show such relationships.

The combination of goals and objectives spell out what you want for your urban forest. They describe your desired destinations. The specific actions describe how you get to those destinations.

An action is a step you need to achieve an outcome, e.g., plant trees, conduct workshops, or enforce regulations. Generate actions for each objective.

Maintain and conserve appropriate trees in a healthy condition through good management and cultural practices.

Objective 2.1

Develop a tree removal and replacement program for poor tree stock and for diseased, declining, and inappropriate trees.

Actions

2.1.1 Develop parameters and create a rating system for evaluating and prioritizing trees for removal.

2.1.2 Rate trees of concern.

2.1.3 Develop a tree removal program.

2.1.4 Secure funding for tree removal/replacement program.

Objective 2.2

Establish policies for tree selection, care and maintenance based on ISA Best Management Practices and ANSI standards.

Actions

2.2.1 Write/adapt standards.

2.2.2 Write tree stock selection criteria.

2.2.3 Provide and review standards/specs and tree stock selection criteria with staff and contractors.

Objective 2.3

Remove invasive tree species from wildland-urban interface landscapes to prevent additional escape into green infrastructure and native riparian areas.

Actions

2.3.1 Prioritize the most invasive tree species for removal.

2.3.2 Certain species will require quarterly applications of an approved pesticide until they are completely dead.

Tools

Tools are things you use to help you take an action. For example: tree inventories and tree ordinance are tools that can be used to help manage an urban forest. You might have to take an action (e.g., purchase inventory software and collect data; or write and pass an ordinance) to make a tool available for use.

Tools and actions will vary with the overall target (tree resources, management, community) and whether management is direct (e.g., maintenance of trees that you manage) or indirect (e.g., improve tree planting practices used by contractors or the public).

A single action can actually require a number of specific steps. Before choosing a given action, you should consider the steps that will be needed to implement it. This will help you compare the feasibility, cost, and effectiveness of alternative actions.

0 Comments