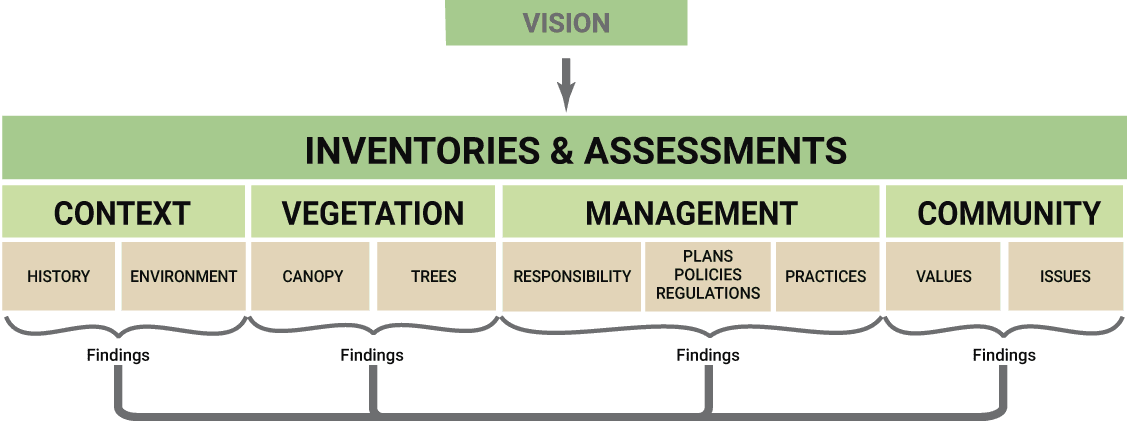

Inventories and Assessments

What do you have? Know where you came from to know where you are going.

- Context

- History and Land Use Changes

- Environmental Assessments

- Vegetation

- Canopy Cover Assessment

- Tree Inventory

- Management

- Responsibilities

- Plans, Policies, Regulations

- Management Practices

- Community

- Values and Issues

The information collected in Inventories and Assessments will be summarized in the plan section: Status of the Urban Forest.

History and Land Use Changes

A review of the history of the urban forest will help explain how it arrived at its current composition and condition. Compare aerial imagery for past and current land uses. Consult your local museum, historical society, or tree care non-profit to learn about heritage trees and past community urban forestry efforts.

It can be helpful to include what is known about:

- native forests

- historical green infrastructure

- significant habitat areas

- plant material uses by indigenous peoples

- evolving urban/wildland interface areas

How has site history affected the development and composition of the current urban forest?

Based on how the urban forest has developed over time (e.g., over use of certain species) what future management issues can be anticipated?

Is there a history of community stewardship of trees?

Are there trees of historical or cultural significance that are important to protect?

Environmental Assessments

Some environmental factors require consideration in making resource management decisions. Assess factors that are relevant to your site, such as climatic conditions that can impact plant selection. Consider:

- climate and global climate change impacts

- general soil types, capabilities and limitations

- fire hazard areas and concerns

- exotic and invasive pests

- invasive tree/weed concerns and land use interface issues

- critical habitat areas and fragmentation: the need for wildlife corridors to connect blocks of habitat

- threatened, endangered and species of concern

- water quality and availability, and more.

Planting sites in urban areas vary with other factors that affect tree growth, including:

- extensive impervious surfaces that cover soil and speed runoff to waterways

- confined root zone space and soil volume

- underground utilities

- need for irrigation

Note: While conducting tree inventories later, consider recording such relevant factors.

What are the important environmental factors that affect tree management, selection and maintenance in the plan area?

How can these factors be taken into account in the urban forest plan?

For site-level plans, are there important conditions to consider? For example, are there mature trees that can be protected during construction and preserved for a residential or commercial development site?

Climate Zones

Climate characteristics can vary across the plan area. Factors to consider include minimum and maximum temperatures, fog influence, and wind exposure.

Climate varies over the years due to cyclical weather patterns such as the El Niño/southern oscillation. Concerns of climate change creating extreme conditions should be considered in long-term planning. Record heat or cold, droughts, floods, or severe storms could have impacts on tree populations that are geared toward average conditions. Providing additional irrigation could be one way to mitigate for increased drought.

Climate change could result in greater stress on our native trees, making them more susceptible to disease and insect attack. With global climate change, native trees might not carry a genetic advantage to meet the changes that come to cities or wildlands. Other imported tree species might be able thrive in more extreme conditions.

For site-level plan areas, significant differences in microclimates might occur between planting sites due to:

- slope and aspect

- shade from buildings or landforms

- windbreaks and patterns

- reflected heat from buildings and pavement.

For some plans, assess microclimates in greater detail as well as soil capabilities and limitations, steepness and aspect of slope, and native and invasive vegetation.

What are the climate zones: USDA and/or Sunset’s Western Garden Book?

U.S. Department of Agriculture Plant Hardiness Zone Map http://www.usna.usda.gov/Hardzone/ushzmap.html

Sunset’s Western Garden Book climate zones http://www.sunset.com/garden/climate-zones

What is the average annual precipitation, extreme and average high and low temperatures?

Is supplemental water necessary for establishment and health of trees? If so, what is the source and quality of irrigation water?

Is it important to plant native or “waterwise” trees species?

Do these factors change in different portions of the plan area?

In larger or more diverse plan areas, soil, microclimate, wind exposure, or other factors may vary across the site. If so, it may be useful to identify zones for tree selection and maintenance. (e.g., zone maps).

Soil Conditions

A variety of soil properties may affect tree selection and performance:

- soil texture (sand/silt/clay balance)

- compaction

- water-holding capacity

- soil drainage characteristics

- depth to water table

- soil salinity

- soil depth

- concentrations of specific toxic ions

What are the general soil types and erosion potential? How could they limit urban forest development and management?

USDA Soil Survey: websoilsurvey.nrcs.usda.gov

California’s site: http://casoilresource.lawr.ucdavis.edu/soilweb-apps

[itg-glossary glossary-id=”436″]Soil survey[/itg-glossary] data can help identify soil limitations, but where soils have been altered through cut and fill or imported top soil, the soil survey data will not apply.

Fire Risk

Wildfire is a main concern for communities that have spread into fire-prone vegetation types. Management of vegetation (fuel reduction) at the wildland/urban interface to reduce fire risk has become an important issue. The UFMP might include elements related to fire risk. For areas with elevated threat ratings, consider how the plan will interact with other documents and plans that already address fire risk. Although vegetation management plays a critical role in reducing fire hazard, other factors, such as building construction and materials are important for minimizing fire risk. Cities and county general plans include a safety element that should be integrated with the UFMP to address wildfire threats.

In California for example, the California State Public Resources Code section 4291-4299 has requirements for creating [itg-glossary glossary-id=”491″]defensible space[/itg-glossary] for structures in lands covered by flammable vegetation. Guidelines have been created by CAL FIRE to help landowners interpret state rules. CAL FIRE has developed a rating of wildland fire threat for the state. The rating is based on potential fire behavior (derived from weather, terrain and vegetative-fuel data) and expected fire frequency (derived from 50 years of fire-history data). Areas are assigned one of four fire threat ratings: moderate, high, very high and extreme. In general, fuel reduction means arranging the trees, shrubs and other fuels sources in a way that makes it difficult for fire to transfer from one fuel source to another. It does not mean cutting down all trees and shrubs, or creating a bare ring of earth across the property.

Is wildfire a concern for the area being planned? If so, in what ways can it be addressed without creating erosion hazards and habitat degradation? Consider better planning/urban design; removal of hazardous invasive plants that carry fire through green infrastructure; ordinances for defensible space that include pruning of “ladder fuels” and removal of selected plants at appropriate distances; mowing grasses instead of disking and disturbing the soil; etc.

Invasive Species

Invasive pests are a growing issue for urban forests, green infrastructure, and adjoining native landscapes. Exotic species are organisms (plants, animals, and microorganisms) that are not native to a particular region. The impact of exotic pests varies considerably depending on the species and the area being invaded.

The introduction of invasive insects may threaten the success of some tree species. The impacts of pests such as the polyphagus shot hole borer, gold spotted oak borer, and walnut twig borer are difficult to predict. Consider the value of a diversified tree-scape for stability of the urban forest.

Search for invasive pest information at the National Invasive Species Information Center (NISIC), https://www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/index.shtml , a gateway to additional resources for your state/area. Find information for your state at sites such as the University of California’s Integrated Pest Management Program at www.ipm.ucdavis.edu/EXOTIC/exoticabout.html .

Urban Forest Management Plans can help control the spread of invasive tree species by ensuring that invasive exotics are not included on planting lists and by encouraging residents to remove invasive weed species from their landscapes.

Many entities, including land preservation organizations, work to restore degraded habitats for wildlife and sometimes to prevent wild fire and flooding. For California, see the California Invasive Pest Council’s (Cal-IPC) Don’t Plant a Pest at http://www.cal-ipc.org/ , which offers regional horticultural alternatives for invasive landscape plants.

Are invasive pests and weeds of concern for the area being planned? If so, assess how the invasive species can be reduced or eliminated to reduce negative impacts.

Species of Concern

If areas within the plan include habitat or buffers for endangered, threatened, or other plant or animal species of concern, evaluate early. Note special considerations as they relate to urban trees and green infrastructure, especially waterways.

Are species of concern dependent on trees/vegetation within the planning area? If so, what management considerations, studies, and procedures will be considered in the UFMP? For example, pruning and disturbance will be precluded from the habitat of sensitive species during mating and nesting seasons.

Consult agencies that are involved in planning and habitat management for the species of concern. In some cases, areas may be part of muti-species habitat management plans.

Other

Include summaries of other relevant environmental concerns that relate to the planning site.

Canopy Cover

Tree canopy cover refers to the proportion of land area covered by tree crowns as viewed from the air. Assess the amount of canopy cover using aerial imagery to get an overall picture of the urban forest. By determining the current canopy cover, you establish a baseline for the range of the urban forest and define canopy cover targets for the future.

Defining canopy cover will help you find opportunities to broaden the urban forest and to determine where management is needed to sustain current canopy levels. Knowing canopy cover helps quantify the [itg-glossary glossary-id=”387″]ecosystem services[/itg-glossary] provided by the urban forest.

Tools: [itg-glossary glossary-id=”386″]itreetools.org[/itg-glossary]

Find the outermost canopy boundaries and measure. What percent of that area is covered by trees?

Compute the benefit of the existing canopy cover.

Can you define canopy cover targets for the planning area as a whole and/or for segments within the planning area (e.g., residential areas)?

How does current canopy cover compare to possible canopy cover targets?

Are canopy cover levels in the parts of the planning area at or near maximum sustainable levels? If so, should these levels be used to set targets?

What factors (environment/trees/management) are associated with the urban forest in areas that have maximum or optimal canopy cover levels?

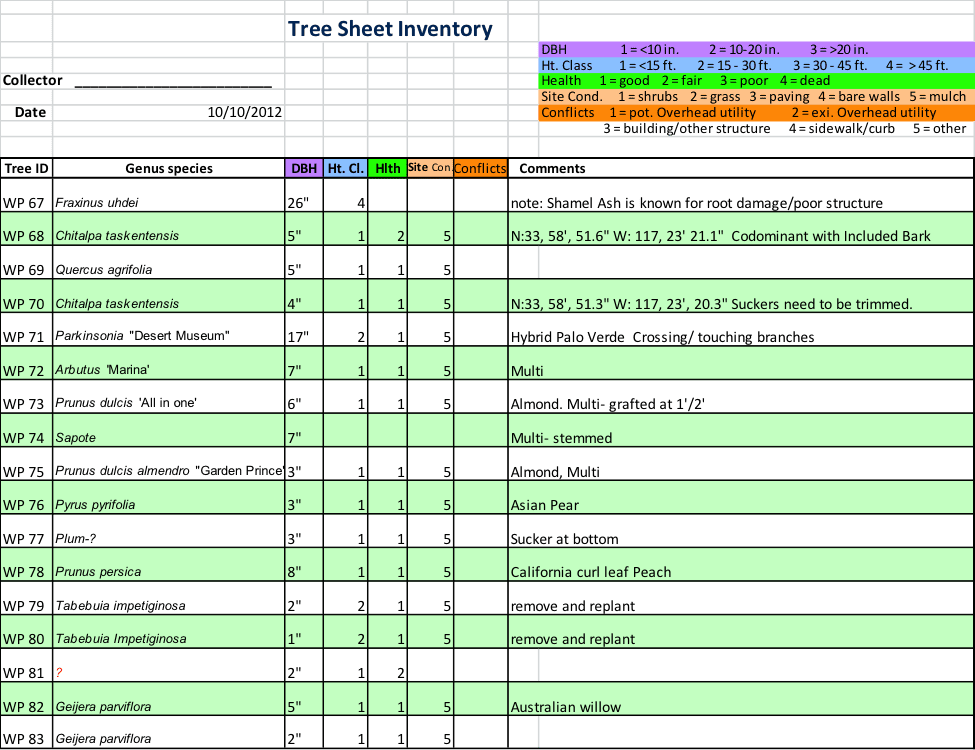

Tree-Vegetation Inventory

Do you have an inventory of the trees, or do you need to make one? Assess the current composition and distribution of the community’s trees.

Having a tree inventory is essential if you manage urban tree populations on a tree-by-tree basis. The data record for each tree typically includes information about tree characteristics, maintenance history, and management needs. The data that is maintained for each inventoried tree will depend on the tree program’s needs, who will be collecting the data, and the role that the inventory plays in the tree management program.

Work toward developing a recent tree inventory that contains the following minimum data for each tree:

- Location

- Species

- Size/age

- Condition

- Management responsibility

What do you want/need to know about each tree? In addition to the list above, consider recording:

- hazard risk

- raised roots

- pruning needs

- irrigation needs

- native species

- heritage trees

- site conflicts, such as powerlines above or constrained roots in planters

- sidewalk damage

- short life span

- failure prone tree

- high maintenance needs

- value

What inventory method will be used?

List of Inventory Management Software

This list, compiled by the U.S. Forest Service, contains lists of commercial software and public domain program

| Tree Inventory | ||||||||

| Collector _________________ | ||||||||

| Date _________________ | ||||||||

| Tree ID | Genus species | DBH | Ht. Cl. | Hlth | Site Con. | Conflicts | Comments | |

| DBH 1 = <10 in. 2 = 10-20 in. 3 = >20 in. |

| Ht. Class 1 = <15 ft. 2 = 15 – 30 ft. 3 = 30 – 45 ft. 4 = > 45 ft. |

| Health 1 = good 2 = fair 3 = poor 4 = dead |

| Site Cond. 1 = shrubs 2 = grass 3 = paving 4 = bare walls 5 = mulch |

| Conflicts 1 = pot. Overhead utility 2 = exi. Overhead utility |

| 3 = building/other structure 4 = sidewalk/curb 5 = other |

Urban Tree Considerations

Street Trees

Due to their location, street trees provide specific benefits not provided by other trees. Benefits include traffic calming and extending the life of roadway pavement. Streets shaded by trees contribute to “sense of place”, which can also contribute to increased community pride and property values.

Street trees are often located in very constrained locations. Pavement and utility lines may limit growing space. Other management issues that may be important for street trees:

- Trees are commonly subject to damage by vehicles and street construction activities.

- Conflicts with utilities, hardscape (especially sidewalks, curbs, and gutters) and other built infrastructure are common.

- Branch, trunk, and root failures commonly have a high potential to cause property damage and/or injury.

- Tree canopies typically need to be maintained for street and sidewalk clearance and to minimize risk of branch failures.

- Falling leaves, seeds, and fruits may create hazards on sidewalks and contribute to storm drain clogging.

- Street trees may generate high numbers of service requests and complaints.

Because of these issues, species selection is often a primary consideration. The species used may be specified in a master planting plan or on an approved species list. The palette of potential street tree species may be limited, which can sometimes lead to low species diversity. Low species diversity can pose a risk to the urban forest if one or more common species develop serious problems. The street tree assessment should look at both species diversity and the overall performance of various species in use.

What types of tree and site data should be assessed/analyzed?

Are necessary data available in an inventory or are surveys needed?

What are the most meaningful ways to stratify tree data: by species, size class/age, condition class, maintenance needs, planting situation?

It is practical or useful to divide street trees into geographic management zones? If management zones have been in use, how well do they work?

How do we identify/quantify empty planting spaces?

Is the long term sustainability of street tree canopy at risk due to a lack of age and/or species diversity?

What is the frequency and severity of conflicts between street trees and other elements of infrastructure (e.g. curbs, sidewalks, overhead lines)?

Facility Trees

Many urban trees fall into the “facility tree” category. These are trees around buildings and other built facilities that are not adjacent to streets. Most trees in sites such as office parks or campuses are facility trees. In cities or counties, facility trees are found around public buildings. Shade provided by trees near buildings can greatly reduce summer cooling costs. Facility trees also modify the visual impact of structures.

Facility trees often grow where soil volume is restricted by hardscape. They commonly occur in landscape beds near structures. These landscape beds can vary widely in size. Facility trees may also occur in small planters or cutouts in sidewalks or plazas.

Some potential management issues:

- Soil near buildings may be unfavorable due to severe compaction and alkaline residues from to concrete, stucco, etc.

- Planting beds may have inadequate drainage or irrigation.

- Competition from other landscape plants may be excessive.

- Reflected heat or excessive shading from structures may affect tree growth and health.

- Pruning may be needed to maintain clearance from buildings and over walkways.

- Potential for root damage to foundations and walkways needs to be considered.

- Underground utility maintenance may damage tree roots.

Assessments should note special management issues. Also consider how tree condition and management vary with distance from structures, planter size, or other factors.

Which departments currently manage facility trees?

Are there maintenance / management issues that are unique to some or all facility trees in the plan area?

Should facility trees be handled separately from other groups of trees in the management plan?

Can we define management zones for facility trees based on planter size, location relative to buildings, or other factors?

Parking Lot Trees

Parking lots occupy large patches of the urban landscape. Trees in parking plots can help mitigate some of their undesirable characteristics:

- Tree shade helps cool pavement. This helps reduce the urban heat island effect that is associated with paved areas.

- Tree shade cools parked cars. Hydrocarbon vapors emitted by hot cars contribute to photochemical smog formation.

- Trees intercept and channel rainfall, reducing runoff and water pollution associated with runoff from paved surfaces.

- Trees screen and soften the visual blight that parking lots pose.

Many communities have policies and regulations designed to increase the amount of tree cover in parking lots. These regulations generally apply to new or redeveloped lots. Relatively few communities have audited parking lots to determine if they achieved the canopy cover specified in the design approved by the Planning Department. An assessment of parking lot tree canopy can indicate whether design policies are effective or need to be changed.

Use aerial photos to assess total canopy cover in parking lots. If you have a series of historical aerial images, you can track changes in canopy cover over time. Many parking lot shading regulations specify the amount of shade required after a certain number of years. Changes in parking lot canopy cover can be correlated with the age of the parking lot, tree species, pruning and maintenance practices, planter sizes, or other factors. Assessing the percentage of the parking spaces that are shaded provides another measure of parking lot shade. You can use ground surveys or high-resolution aerial photos to estimate shading of individual spaces.

Parking lots are typically poor areas for growing trees. Trees are often grown in small cutouts with compacted soils, poor irrigation, and inadequate drainage. Trees may be subject to heat damage from hot pavement and vehicle engines. Trees are also damaged by vehicles and shopping carts. Trees are pruned to provide vehicle clearance and avoid blocking parking lot lighting. Retailers sometimes have trees pruned inappropriately to enhance visibility of signs or buildings from the street.

Assessments related to management issues may include:

- empty planting spaces

- species

- condition, including damage

- planting site dimensions.

What is the planting site size?

What is the number or percent of empty planting spaces?

What is the parking space to tree ratio?

What percent of parking spaces are shaded? Use shade categories (e.g., <10%, 10-50%, >50%) to show degree of shading in shaded spaces.

Park Trees

Park trees include trees in public parks maintained by cities, counties, parks districts, and the like. Park-like sites may also exist in open areas of campuses, botanical gardens, and other private or public locations.

Parks of similar age may be similar in makeup and management and can be considered as a group. For initial data collection, you may only need to do sample surveys of representative parks in each group. You can use sample surveys to gather data if you lack an inventory.

Compared with street or facility trees, park trees have fewer space constraints for both canopies and roots. This can allow the use of a wider range of species and larger trees overall. However, tree care may not receive high priority where turf or sports fields are primary uses. Crews that maintain lawns may not have adequate training to recognize and address tree maintenance issues.

Other considerations:

- Trees in or near lawns can compete strongly with young trees.

- Soil compaction due to foot and equipment traffic on wet soils may impair root growth and drainage.

- Surface roots in turf may conflict with mowing equipment and may pose tripping hazards.

- Trees can be subject to damage from mowing equipment and park users. This can make it difficult to establish new trees.

- Hazard management may be a primary concern, especially in areas that are heavily used.

- Newly–developed parks often start with even–aged stands of trees. Phased tree replacement and inter-planting may be needed to avoid a future replacement of the entire stand.

- Parks may include heritage trees or other old or unique trees with special maintenance needs.

As an example, the inventory for Fort Greening Park in New York City was conducted focusing on the following elements:

- Tree spatial distribution

- Species diversity and composition along with disease and pest problems of some species

- Tree size distribution

- Tree condition

- Formal landscape features

- Growing conditions

- Human damage

- Historic trees

What maintenance and management issues are common in park sites?

Which parks need to be treated individually for planning purposes?

Can we create useful groupings of park sites based on location, year of construction, or other factors?

What roles do trees play in various park sites?

Heritage Trees

Do you have trees that have cultural and historical significance, e.g. trees that were planted when the area was first settled or developed? Because these are special trees by definition, they can have special needs relative to tree care activities and inspections. The evaluation of heritage trees should include whether inspection and maintenance is adequately matched to the trees’ needs.

Some communities have enacted [itg-glossary glossary-id=”412″]heritage tree[/itg-glossary] ordinances or other regulations to protect significant local trees that are on private and public property. Heritage tree ordinances vary widely. A discussion of various factors used to define heritage trees can be found at the ISA Guidelines for Developing and Evaluating Tree Ordinances, pages 166-168. In jurisdictions that have heritage tree ordinances, it is important to assess the effectiveness of the ordinance to see whether it is accomplishing its intended goals. Assessments may include examining permits related to retention of heritage trees and selecting a sample to see how trees have fared in the years after the permitted activity.

Trees planted as mitigation could also be inspected after a number of years to see if they are still in place and how much of the lost canopy is actually replaced over time. Aerial imagery can be used to track individual trees over time. Aerial photos can provide information on canopy size and can be used to detect evidence of significant canopy decline in large trees.

If heritage trees form an important component of a community’s urban forest but do not have any regulatory protection, protection of these trees via an ordinance or other regulations may be considered in the plan. Information on the numbers of heritage trees, their condition, and trends affecting them can help to determine whether and how this segment of the urban forest resource should be addressed.

Are there “heritage” trees or trees of historical or cultural significance that are important to protect?

Which trees are affected by the permit process or design review?

What are the reasons for permit requests?

What heritage trees have been removed? Reason for removal?

What is the amount of mitigation for removed trees? e.g. money and/or trees planted.

Did mitigation trees survive?

Open Space Trees

Tree management in open spaces is usually less intensive than in other parts of the urban forest. In some areas, open space trees may be largely unmanaged. However, these stands can and will change over time.

Active management may be needed to:

- help maintain native stands that have low levels of natural regeneration

- suppress exotic species that may crowd out native trees in riparian areas

- replace flammable exotic species with lower risk, native trees such as native oaks.

Unless the stand is very small, a complete tree inventory of open space trees may not be practical or necessary. You will normally collect data on open space trees at the stand or forest level. Canopy cover can be assessed using aerial images. Use sample surveys to collect information about species, size classes, condition, regeneration and other factors of interest.

Is the composition of existing native trees a factor to consider?

What is the overall health of forests/woodlands in our open space areas?

What changes have occurred in these stands?

What changes are likely to occur over time under current management practices?

How do current and projected uses of the open space and surrounding properties affect the management of the forests/woodlands?

Are there information gaps related to management of open space stands?

Are there other vegetative components that are important to assess?

Is conservation of existing native trees a factor to consider, such as along a waterway? What is or would have been the native vegetation/trees?

Are there interface issues between urban, agriculture and/or habitat lands, such as escaped exotic species or landscaping with invasive species?

Responsibilities

Urban forest managers typically:

- plan and implement tree plantings

- maintain existing trees

- manage hazards associated with declining trees

- remove trees that have reached the end of their useful life span

- recycle or dispose of green waste and wood from pruning and removals

Urban forest managers must also deal with problems related to the urban environment.

In some organizations, tree care may be divided among several different departments. Determine where the responsibilities lie, and with whom. Review the roles of each person and department.

Assess how various departments interact with each other and with the community, tree committees, parks commissions, and other organizations involved in tree care.

How are activities of different entities coordinated and monitored?

Are the various entities that affect trees working with the same vision and toward the same end?

Are all units supporting the overall management goals through their activities?

Which entities regulate or affect segments of the urban forest? (e.g., tree committees, city councils, boards of supervisors, planning commissions, or land use committees)

Do these entities and tree managers take advantage of partnering with organizations and concerned citizens for the benefit of the urban forest?

Who educates the public about the urban forest and tree care regarding both private and public property?

Which entities perform activities that affect the urban forest? In relating to:

- tree health

- growing space

- utility line clearance

- damage to sidewalks and other hardscape due to tree roots

- construction damage to tree roots

- exotic species invading natural areas

- fire hazards at the urban/wildland interface

Which departments have direct tree care responsibilities and what portions of the urban forest do they manage?

Are the assigned roles and responsibilities providing for efficient and effective management of the urban forest? Evaluate the pros and cons of shifting responsibilities and in-house vs. contracted work.

In what ways, if any, could efficiency be improved? (Combining units, sharing equipment, or partnering with other departments or organizations)

Assess for each unit/department that has direct tree care responsibilities.

Are there adequate staff, training, and budget to provide for tree care needs?

Does retention rate affect program capabilities?

What inventory and work scheduling system is used? How well does it work?

| Activity | Activity subclass | Arborist | Public Works | Parks | Planning | Other: specify |

| Planting | New sites | |||||

| Replacement plantings | ||||||

| Pruning | Scheduled | |||||

| Storm/emergency | ||||||

| Utility clearance | ||||||

| Street/equipment clearance | ||||||

| Tree removal | Hazard trees | |||||

| Clearance (for flood control, fire safety, etc) | ||||||

| Root system work | Sidewalk/curb repair and replacement | |||||

| Excavation for utilities | ||||||

| Construction | ||||||

| Permitting | Planting | |||||

| Pruning | ||||||

| Removal | ||||||

| Outreach/ education | Property owners/public | |||||

| Contractors |

Plans, Policies, Regulations

Review organizational records, including prior plans, policies, and ordinances. Cities and counties, as well as other public entities typically have multiple layers of planning documents. These may include a general plan, specific plans, an open space element, design and landscaping guidelines, watershed plans, a [itg-glossary glossary-id=”967″]climate action plan[/itg-glossary], etc.

How will the UFMP be related to other plans and regulations?

Is there an urban forestry or green infrastructure component in other plans?

Do any plans need to be amended/updated to reference the UFMP or to ensure compatibility?

Plans

Are there urban forestry components in other plans? Which documents (city codes, general plan, specific plans, design and landscaping guidelines) include tree-related guidelines and regulations?

Planning goals can be mutually reinforcing. For example, if a community adopts the concept of preventing forest fragmentation, the corollary is to adopt land use practices that do not allow development projects to cut up the forest, but instead consolidate urban growth in compact, contiguous development patterns.

Are notifications, design consultation, and oversight adequate to protect trees from harm?

What will be the relationship of the UFMP to other planning documents?

Policies

Are there tree-related policies? If so, are they current?

Are policies followed?

Regulations

Are there any regulatory measures pertaining to parts of the urban forest?

For example, you might discuss the need to limit pruning during nesting season and/or to employ tree care professionals that are trained to recognize nesting sites: Migratory Bird Act.

Are local tree trimmers required to have “Wildlife Aware” type training to prevent bird nest disturbance during nesting season?

Which areas or classes of trees are subject to regulation?

How would regulations impact management? For example, do regulatory agencies such as U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, water quality control boards, or fish and wildlife agencies, require permits before pruning/clearing can be conducted in certain riparian areas?

Are there tree care ordinances?

What is the impact of existing regulations on targeted tree populations (e.g., street trees, heritage trees?)

To what degree are ordinances/regulations enforced? Possible measurements might include number of permits, violations, citations issued, penalties or fines collected.

Do ordinances need evaluation/revision?

Do state or federal regulations (e.g., California’s AB32, The Global Warming Solutions Act) need consideration in regard to management of the urban forest?

| Tool | Street trees | Park trees | Facility trees | Heritage trees | Parking lot trees | Other: specify |

| Ordinance | ||||||

| General plan | ||||||

| Specific plans | ||||||

| Improvement standards | ||||||

| Specifications – planting | ||||||

| Specifications – pruning | ||||||

| Hazard program | ||||||

| Street tree master plan | ||||||

| Approved planting list |

Refer to Guidelines for Developing and Evaluating Tree Ordinances

Overall, does the regulatory framework need to be expanded or updated?

Are guidelines consistent throughout all documents?

Do any of documents need to be amended or updated to ensure compatibility and reference the UFMP?

Management Practices

Knowledge of past practices and events is key to understanding the present condition of the urban forest.

Almost all processes needed to sustain the urban forest—establishment, growth, decline, death, and degradation of trees—require some level of active management. In this section, determine what programs and tools have been used to date, and how effective they have been. Review past operations.

Are best practices employed for the sustainable management of the urban forest?

Are standards and practices up to date based on the best available information and research?

Is there adequate species and age diversity within the urban forest?

Are declining trees evaluated for risk? Are hazards removed?

How are trees maintained and what is the duration of the maintenance cycle?

When each tree has reached the end of its useful lifespan, is biomass reused and at its “highest and best use”?

[itg-glossary glossary-id=”287″]ANSI A300 standards[/itg-glossary] and corresponding best management practices are the generally accepted industry standards.

What management actions would be needed to reach target canopy levels?

Conduct an audit of past tree care practices to determine which have been successful and which are problematic. For each unit that has direct tree care responsibilities, ask:

How are decisions made relative to tree selection, placement, maintenance, and removal?

Are practices and standards used, including inspection, maintenance, and notification?

Are you able to adopt/update standards available from government (e.g., CalFire), industry (e.g., ANSI), and professional (e.g., International Society of Arboriculture) sources? Would you need to modify or append these standards to account for local conditions?

Is there adequate equipment? Consider the condition, maintenance, and expected service life?

Review the schedule for trees being planted, maintained/pruned, and removed. Are most of the pruning and removals on a scheduled or unscheduled basis, such as response to calls or weather events? It’s generally more cost effective to schedule regular maintenance proactively than to have to react to situations as they arise.

Is there an adequate budget and funding to achieve sustainable urban forest management? Assess your funding sources and consider additional opportunities. Potential sources for municipal programs include:

- Citywide assessment district

- Fines from ordinance violations

- Tree removal permit mitigation fees

- General fund

- Grants (for one-time or infrequent expenses)

- Community groups

- Corporate/local business sponsorships

- Partnerships with utilities

- Gas tax

None of us is as smart as all of us.

— Kenneth H. Blanchard

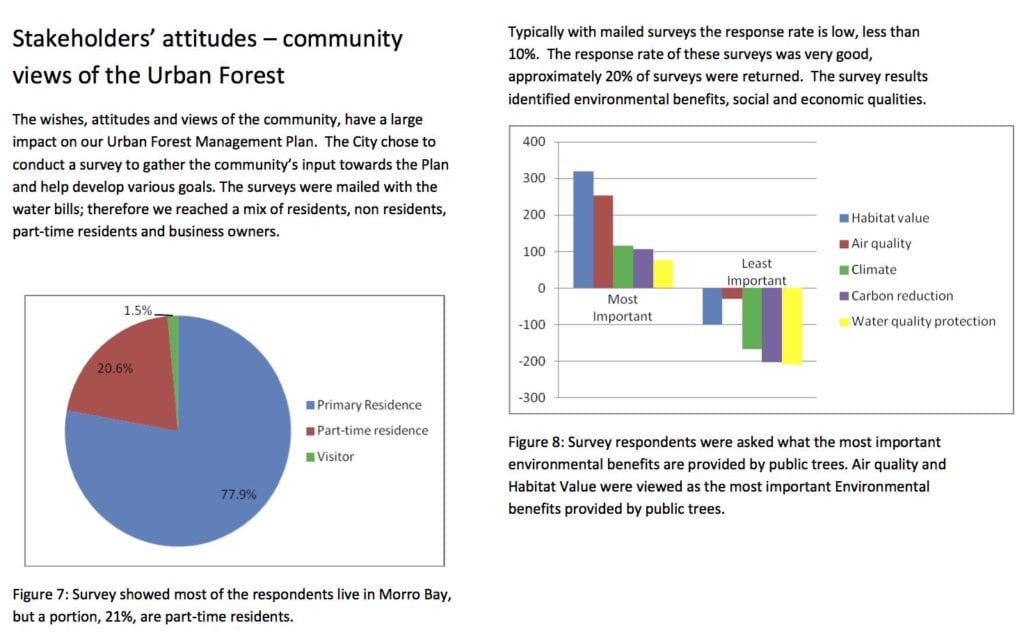

[itg-glossary glossary-id=”500″]Stakeholder analysis[/itg-glossary] is the process of identifying those affected by a project and analyzing their attitudes towards the project and potential changes. Do some brainstorming with others to help identify stakeholders: staff, agencies, groups, businesses, and concerned residents.

Who are the key people and groups that are impacted?

Who are the people and groups whose support you will need?

Who might be good at helping to develop or review the plan?

Which stakeholder groups are likely to influence the success of the plan?

Are these people aware of urban forestry, community concerns, and the specific needs of the area to be planned? If not, how will you educate and engage them?

1. What are the three (3) most important benefits of trees?

❑ Clean the air by absorbing pollutants

❑ Create more pleasant neighborhoods and business districts

❑ Increase property values

❑ Provide food and shelter for wildlife

❑ Reduce greenhouse gases, summer temperatures and address climate change ❑ Shade buildings and lower energy bills

❑ Shade streets for walking and parks for playing

❑ Stabilize soil and reduce storm water runoff

❑ Other_______________________

2. In your neighborhood, are there are too many or too few public trees?

❏ Too few trees

❏ Too many trees

❏ Enough trees

3. In your neighborhood, where do you think more trees should be planted? (Name the streets or areas)

4. What are your top two (2) concerns relating to tree planting and care?

❑ Sidewalks and pavement cracking

❑ Leaves and fruit dropping/ongoing maintenance

❑ Tree roots and underground pipe problems

❑ Blocking traffic, sidewalks, signs, and/or street lights

❑ Creating safety problems from trees and limbs falling

❑ Attracting bugs and other pests

❑ Trees cost too much money

❑ Other _____________________

5. What are you willing to do to ensure San Diego’s trees are maintained and protected for future generations? Check all that apply.

❑ Support new legislation or rules about planting and tree protection

❑ Plant new trees on my property when trees die or need to be removed

❑ Increase the City’s budget for tree planting and maintenance

❑ Volunteer to plant and maintain trees on public property

❑ Support a 1% fee or tax, dedicated to tree care and maintenance

❑ Other _____________________

6. Why are trees important to you (personally) and your family?

7. Other comments and suggestions for the City of San Diego regarding tree planting in urban areas?

Name ________________________________________ Email ___________________________________________ (optional)

Example from City of San Diego

| Question 1: What are the three (3) most important benefits of trees? | % total |

|

49% |

|

53% |

|

11% |

|

26% |

|

45% |

|

28% |

|

35% |

|

24% |

|

2% |

| Question 2 = In your neighborhood, are there are too many or too few public trees? | |

| Too few trees | 68% |

| Too many trees | 2% |

| Enough trees | 24% |

| Question 4: What are your top two (2) concerns relating to tree planting and care? | |

|

53% |

|

29% |

|

28% |

|

16% |

|

9% |

|

3% |

|

5% |

| Other: Watering and water costs | 6% |

| Other: Maintenance, trimming, and pruning | 3% |

| Other: Fire hazards | 2% |

| Other (not identified) | 12% |

| Question 5: What are you willing to do to ensure San Diego’s trees are maintained and protected for future generations? (check all that apply) | |

| a. Support new legislation or rules about planting and tree protection | 52% |

| b. Plant new trees on my property when trees die or need to be removed | 54% |

| c. Increase the city’s budget for tree planting and maintenance | 49% |

| d. Volunteer to plant and maintain trees on public property | 34% |

| e. Support a 1% fee or tax, dedicated to tree care and maintenance | 28% |

| f. Other (none) | 10% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Values & Issues

Ask stakeholders, including decision-makers, about their concerns, desires and perceptions regarding the urban forest. Use tools such as interviews, surveys, and focus groups to understand the prevailing attitudes.

- Small area example: Meetings and interviews may be adequate assessment tools.

- Large area example: Consider hosting meetings for representative focus groups and interview interested community members, leaders, and tree-care experts. Use public polling methods and social media to assess larger samples of the population. Today, Survey Monkey is a commonly used online tool. Other options include interviews by telephone, mail surveys, and interviews in public areas or door-to-door.

On the toolkit site, see examples of surveys, responses, feedback, and survey results.

Determine the specific issues that are relevant to your plan to include in the stakeholder attitude assessment. Also, use a survey to help determine if awareness and education are needed regarding urban forest benefits, management, and tree care.

[itg-glossary glossary-id=”773″]Survey writing skills information[/itg-glossary] To learn how strong attitudes or opinions are, incorporate rating levels (1 to 10) and “what-if?” scenarios.

Summarize inventories and assessments for the “Status of the Urban Forest” section of the UFMP.

You can include the detailed inventories, sample surveys, and assessments in the appendices. After surveying stakeholders, summarize the concerns, desires and perceptions of stakeholders regarding the urban forest.

Is there a stewardship ethic in the community for urban forestry?

0 Comments